Blue Chip Pharma Investing Part II: Looking for Long-Term Winners

In Part I we looked at the challenges and opportunities for pharmaceuticals businesses and investors. In this Part II, we will discuss our approach to pharma investing through the examples of Roche and Johnson & Johnson – two big holdings in the Huntress Global Blue Chip Fund.

Our approach is to face the challenges head-on. We suspect that investors may not always give enough credit to those companies that grasp the nature of the challenges by going out of their way to: a) entrench long-term thinking and b) create and preserve a culture where innovation is more likely to flourish. It must be said however that these cannot by themselves guarantee success. We are well aware that serendipity also plays a frequent role in drug discovery; but as Louis Pasteur said: “chance favours only the prepared mind”. We like businesses that acknowledge this truth and embrace it – the prepared mind, serendipity and innovation often seem to go hand in hand.

Detail from Portrait of Louis Pasteur by Albert Edelfelt, in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris

While Roche and J&J have been in continuous operation since the 19th century and share some traits, their methods for entrenching long-term thinking differ. Both have also been among the very largest pharma companies in the world since at least the 1960s in the case of Roche, and the 1980s in the case of J&J. But note that they have been practically alone in not needing to participate in any of the transformative mega-mergers, common since the 1980s – a major reason why they still have attractive returns on capital.

Roche – the patient capital model

F. Hoffmann-La Roche & co was established in 1896 by Fritz Hoffmann, in Basel, Switzerland where the company remains today. The “La Roche” part was the family name of Hoffmann’s wife, while the short form “Roche” has been used to identify the company almost since the beginning. Since its founding, Roche has been at practically every step in the evolution of the modern pharmaceuticals business from being among the first to standardise mass production of preparations and extracts to leading the charge in the biotech revolution. Today Roche is the largest biotech in the world.

Save for a 20-year period following Fritz’s death in the 1920s, the company has been continuously controlled by his descendants. But notwithstanding family control, the last Hoffmann to actually run Roche was Fritz until he stepped down in 1919. As the late Paul Sacher, a family member and non-executive director from 1938 to 1996, wrote in 1995:

No member of this family has ever attempted to influence the company’s fortunes purely to his own advantage, or to play an inappropriate role. I hope that will never change. The descendants of Fritz Hoffman-La Roche know their limits and duties, which may at times call for personal sacrifices. Only sensible restraint will allow us to maintain the harmonious and productive interplay between company and family.

- Roche – A Company History – 1896-1996, H.C. Peyer (1996), forward

Most of the family’s shares are held in a collective pooling arrangement that dates back to 1948, and the family is now on its fourth and fifth generation of shareholders. They currently have two non-executive directors on the company’s board, both serving since 1996. Per André Hoffmann, great-grandson of Fritz and the head of the collective pool:

We have always proceeded on the assumption that what is good for the company is good for the family. Not the other way round.

I always quote three numbers to bring some perspective to our ownership. One is eight, the number of family shareholders in the pool. Two is 91,000, the number of employees at Roche. And three is 23 million, the number of people that took our current drugs last year. For us, there is absolutely no contest: the interest of eight people is nothing compared with the other numbers.

- Both quotes taken from the EY Family Business Yearbook 2016, pp174 - 175

Make a note of these sentiments, as we will see echoes of the same when we come to J&J. But the main point I want to make here is that when the majority of Roche’s voting share capital is controlled by a family more concerned about passing the company on in a healthy state to the next generation than with short-term profitability, it becomes much easier for management to think in terms of 20-year cycles. This is not to say that management always get things right, but the long-term thinking is evident.

My favourite example of the latter is Roche’s investment in San Francisco-based Genentech. Genentech is the original pioneer of the modern biotech business. Founded in 1976 and famed for its science-driven and free-spirited culture, Genentech is the most prolific biotech, and consistently cited as among the most innovative. But in the late 1980s Genentech needed lots of extra capital to get its pipeline to market, and the founder Bob Swanson wanted this to come from a partner with similar ideas. Not finding this in the US, he approached Roche who agreed to acquire a 60% stake and make an infusion of $500m for a total investment of over $2bn. Certainly an eyebrow-raising investment at the time, Genentech would not produce its first major hit until the launch of Rituximab in 1997 or show any material profits until the mid 2000s. Recall that normally when big pharma makes a big external investment, it is to get an immediate boost to the top line – not so at Roche, where they think in decades.

Ownership has since been increased to 100%, but what has always been constant is the companies’ mutual insistence that Genentech operate independently such that it may retain its culture – which along with patient capital has been the secret of its success. Genentech was very much the iconoclast when it sought to create a hybrid culture bringing together the best of scientific academia and entrepreneurship in the name of creating medical breakthroughs. Scientists would be able to carve out a pure research career, publish their work and even spend 15% of their time on their own projects (the latter idea was borrowed from 3M). Through our investigations we are satisfied that Genentech does retain its culture, as evidenced for example by an average tenure of over 20 years among its most senior scientists and by Genentech’s continuing lead in developing breakthrough therapies. Today Genentech accounts for substantially more than half of Roche’s $54bn in annual sales.

Roche’s CEO Severin Schwan actually sees his main job as creating an environment where innovation can thrive – whether at Genentech or the company’s three other R&D centres. Schwan also sees his company as having a contract with society – Roche takes financial risks to come up with innovative medicines, and society is happy to give Roche time-limited rewards, after which the medicines become very cheap for the greater good.

Johnson & Johnson – the Credo model

J&J’s beginnings were in surgical dressings rather than pharma. However today pharma accounts for almost 50% of sales and more than 60% of profits. Even without its sizeable consumer healthcare and medical devices divisions, J&J is still a top five pharma company, and for these reasons we consider it a pharma company more than anything else.

Founded by Robert Wood Johnson and his two brothers, J&J opened for business 10 years before Roche in New Brunswick, New Jersey, where it too remains today. But it was the founder’s son, Robert Wood “General” Johnson II, who ran the business for over 30 years and had the most lasting impact to make J&J it what it is today.

J&J spent the first half of its life as a family-controlled business, but for various reasons this was not to last. Instead J&J’s lasting success has at its foundation an ideology that permeates the entire business, and even pre-exists the company’s involvement in pharma: the famous J&J “Credo”. The Credo was penned by the General in 1943. It developed from his deep-held convictions and was based on his earlier writings from the height of the Great Depression in the mid 1930s, when despite his great wealth he became a well-known proponent of reform in corporate America:

Out of the suffering of the past few years has been born a public knowledge and conviction that industry only has the right to succeed where it performs a real economic service and is a true social asset. Such permanent success is possible only through the application of an industrial philosophy of enlightened self-interest. It is to the enlightened self-interest that its service to its customers comes first, its services to its employees and management second, and its service to its stockholders last.

- Johnson & Johnson: A Company That Cares, Lawrence G. Foster (1986), p109

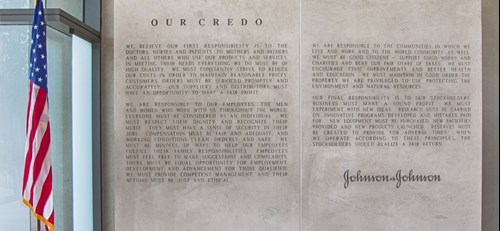

The idea of a modern CEO putting shareholders’ interests last sounds mildly eccentric in the age of shareholder “value” and “activism”, although the General was certainly ahead of his time as regards corporate social responsibility. The Credo itself is a longer document, with several updates since 1943 (including in 2018 for its 75th anniversary). It begins by prioritising the company’s responsibility to “the doctors, nurses and patients, to mothers and fathers and all others who use our products and services”. Then down the paragraphs, after employees, you will also find responsibilities to communities and the environment. But right at the end:

Our final responsibility is to our stockholders. Business must make a sound profit. We must experiment with new ideas. Research must be carried on, innovative programs developed and mistakes paid for. New equipment must be purchased, new facilities provided and new products launched. Reserves must be created to provide for adverse times. When we operate according to these principles, the stockholders should realize a fair return.

Consider that J&J shareholders have done significantly better than the stock market over 40, 30, 20 and 10 year periods - not a bad outcome to say they come last in the company’s list of priorities! And we suspect that a good part of this success is attributable to J&J’s board, management and employees continuing to adhere to the Credo; now 75 years after it was put on paper – at J&J HQ in New Brunswick it is literally set in stone! The Credo is displayed in 800 J&J buildings around the world, in both the reception lobby and meeting rooms as standard practise, and has been translated into 49 languages. But of course, this is not to say that shareholders are not considered at all –senior management’s compensation is, in part, linked to J&J’s relative shareholder returns over rolling three-year periods.

Source: Johnson & Johnson

Since entering the pharma market in the late 1950s, J&J has excelled by prioritising other interests above the shorter-term concerns of shareholders; and in doing so has achieved a similar effect to Roche in its commitment to long-termism and innovation. J&J’s 1961 acquisition of a small but highly innovative Belgian company, Janssen Pharmaceutica, has parallels with Roche’s acquisition of Genentech. Founder, “Dr Paul” Janssen was one of the 21st century’s all-time great drug discoverers, and stayed with the business until retirement in the 1990s. Still operationally independent to this day, Janssen has become one of the largest and most prolific pharma companies in the world. Numerous current employees worked with and were mentored by Dr Paul, including J&J’s chief scientific officer Dr Paul Stoffels. Dr Stoffels, sees his company’s relationship with society, much in the same way as Roche:

“The answer to economic pressure is innovation. If you bring innovative new drugs into the market, society will be prepared to pay for it. We need to produce more and more significant innovation to be reimbursed by the payers in the world.”

Roche and J&J have differing approaches when it comes to R&D, and we could spend many additional words on this topic. But it seems clear to us that both acknowledge the fundamental importance of innovation to the long-term sustainability of their business and its importance in addressing unmet medical need; while their distinct governance structures provide an environment that facilitates persistence in long-term thinking. None of this is to say that the models are infallible or the execution flawless – notably Roche had some set-backs to its business in the 1970s, while J&J has been working through some much-publicised issues of its own in recent years. Nevertheless, the models at Roche and J&J have been more robust than most and we see them as a way for addressing the challenges and exploiting the opportunities of the pharma industry. We aim to look at all pharma investments in a similar way.