Blue Chip Pharma Investing Part I: The Challenges and Opportunities

Within the Global Blue Chip team our aim is to make long-term investments in profitable, growing businesses with enduring competitive advantages. If we can find such a business in an industry with powerful tailwinds, then we consider this to be the foundation of a solid investment. From this perspective we think the pharmaceuticals industry shows a lot of promise, but it’s not without its challenges.

With pharma companies constituting more than 20% of the Global Blue Chip portfolio, this is the first instalment of a two-part note intended to give you a better idea of our approach to investing in this sector. This part will consider the challenges and opportunities for pharma companies and investors generally, and the second part will provide an overview of two of our preferred companies that we believe have developed superior models for addressing the challenges and exploiting the opportunities.

The Challenges

The core “problem” for an established pharmaceuticals business is how to replace lost sales after the patent protection on its medicines expires. When thinking about this we keep coming back to something Sir George Buckley said a couple of years ago in an interview with the Times. Buckley is a well-respected former CEO of 3M, an innovative business we like very much and hold in the Blue Chip fund. Here’s the relevant passage:

“Every company in the world is dying. The core of its business is dying because of competitive attacks, the end of life of its products and maybe even the cannibalisation of its own products.”

The trick, he said, is knowing it, calculating how fast you are dying and then working out how much more stuff you need to put in at the top to counteract what is leaking out at the bottom. “If you only focus on short-term results and not on replacing that core or expanding your capabilities, then you die.”

Buckley is not a pharma executive, but this description is especially fitting for our subject. Consider that patent protection for a new medicine generally lasts 20 years from the filing of an application, but the greater part of the first ten years is spent getting the medicine through clinical trials and regulatory approvals - a process costing billions of dollars, and with no guarantee of success. Assuming no superior medicines arise in the interim, you’re left with perhaps a little over 10 years in which to have a shot at super profits, after which competitors enter with copycat drugs and cause a typical 90% drop in your prices. Meanwhile the challenge of managing constant reinvention over 20-year cycles is magnified when you consider that business leaders retire or get pushed out, research scientists are poached by competitors and impatient investors sell their shares on short-term concerns. When the key constituents often come and go through a revolving door, how can a business maintain the continuity, culture, discipline and self-confidence to innovate at the cutting edge, while making the decisions today that might not bear fruit for 10 years or more? Pharma is a tough business.

But we see the “problem” of the patent system as an opportunity to create a competitive advantage, and a way to sustain and grow super profits in the long term. Abraham Lincoln once said that the patent system “adds the fuel of interest to the fire of genius, in the discovery and production of new and useful things”. It’s no surprise that most of the medicines that have been invented in the last 100 years originated in the country of Lincoln, with its entrepreneurial culture, leading universities and patent system. Most of the rest came from Western Europe, where the dynamics are comparable. The real problem is that the companies that are able to maintain the “fire” are rare – i.e. the repeat innovators.

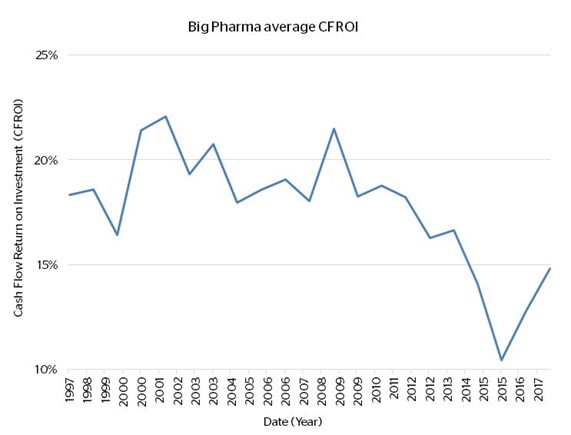

To try to visualise the long-term nature of these challenges for pharma companies and investors, we looked at the 20 largest pharma companies in the world at the turn of this century, as measured by revenue. Of these, we took the 11 listed US and European companies that have existed continuously since then – there would be 16 were it not for various acquisitions and spin-offs in the intervening years. In short, this group constitutes the bulk of what is often called “Big Pharma”. Then we charted their combined cash flow returns on invested capital over the last 20 years; this being one of our preferred metrics for gauging the value created by a company for shareholders. We generally consider a number in the teens or higher to be promising.

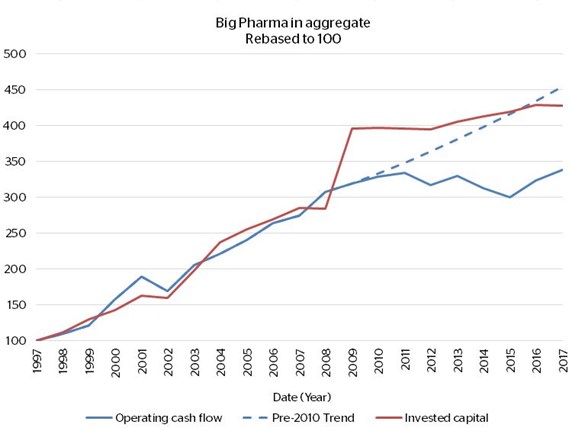

Notice in the first chart, longer-term returns in the high teens to low twenties, followed by a drop-off starting after 2009. Despite an uptick in CFROI in the last two years, the second chart shows that Big Pharma’s aggregate operating cash flows are little higher than 10 years ago, despite invested capital staying more or less on trend.

There are two interesting points to note from this exercise. First, of the 11 companies, all of them remain among the top 20 largest pharma businesses in the world today (actually, 8 are in the top 10) – indicating long-term staying power for incumbents. Second, to stay at the top these companies have had to deploy ever greater amounts of capital. It comes back to the challenges discussed above and the steps taken “to counteract what is leaking out the bottom”. Only those companies that innovate and are efficient in doing so maintain attractive sales growth, cash flow growth and returns on capital over the longer-term – a pool of companies that is limited. The rest must either “buy in” innovation by acquiring other companies, and this tends to be competitive and expensive; or sink ever larger sums into sub-optimal R&D programs in the hope that something turns up.

In addition to acquisitions and heavy R&D investment, it is quite typical for pharma companies to compensate for a lack of innovation by simply raising their prices once or twice a year. We try to avoid companies focussed on growing this way, not only on ethical grounds but because such strategies are unsustainable in the longer term.

The Opportunities

Let me now take a step back to highlight two trends that get us excited about the prospects for the better companies. First, the global population is growing and people are living longer. And when you consider that perhaps two thirds of diseases do not have a cure and many have an inadequate one, there is a huge unmet medical need that imposes an increasing burden on society and its healthcare systems. For businesses with the ability to produce innovative medicines, this represents a correspondingly huge opportunity, as society has proved quite willing to pay for genuine breakthroughs. Indeed, when the industry is at its best it forms a virtuous circle, where the interests of business, investors and society are aligned. You can see the effect of this in real world – in the US about 85% of all prescriptions are now for cheap unbranded versions of once-innovative, but no longer patent-protected, medicines.

The second trend relates to a confluence of advances in drug discovery. The biotech revolution of the last several decades, and the sequencing of the human genome, have catalysed a number of such advances, the two most important of which I shall touch on. First is the advent of “biologics”, complex molecules produced biologically, as opposed to simpler chemical molecules that formed the basis for almost all 20th century medicines. Biologics have made possible a wave of revolutionary therapies, including, for example, a growing number of immuno-oncology drugs which help the body’s own immune system to attack cancer cells. The second advance is in the basic architecture of discovery: a move from mass random screening of various chemical molecules in the hope of finding one that treats disease; to what is called “targeted drug discovery” – the basic idea of finding molecules (chemical or biologic) that bind selectively to targets (i.e. “receptor” proteins) and provoke a desirable action in the human body. For years the number of well-understood targets was low, and this meant that pharma companies tended to go after the same ones; resulting in a spate of low-innovation “me too drugs”. But now, the understanding is much greater and there is an abundance of validated targets, not least due to a much improved understanding of the human genome.

Consider that 20 years ago there was a mere handful of targeted therapies used in the treatment of cancer (including just one biologic – Roche’s Rituximab); today there are around 80 (of which around a third are biologics). When the Human Genome Project was completed in 2003, it had cost three billion dollars over nearly 15 years to map the human genome for the first time. In 2018 anyone can have their genome sequenced within days at a price of less than $1000, and the cost will continue to decline, perhaps to as little as $100 according to the company that makes most of the sequencing machines.

The pace of change has been extraordinary, and such is the state of affairs now that hundreds of thousands of people are having their genomes sequenced every year. When attached to anonymised patient records, this has become an incredibly powerful tool in the search for disease targets. And the targets and molecules being examined today form the basis for the breakthrough therapies we’ll likely be seeing in the mid-2020s onwards – these are the sorts of long-term tailwinds we like. Moreover, I haven’t even discussed cutting edge developments in R&D technologies, new treatments (such as advances in cell and gene therapies, bispecific antibodies and RNA interference) or IT and data analytics – all of which play an integral role in forming what is probably the most bountiful environment for healthcare innovation in years.

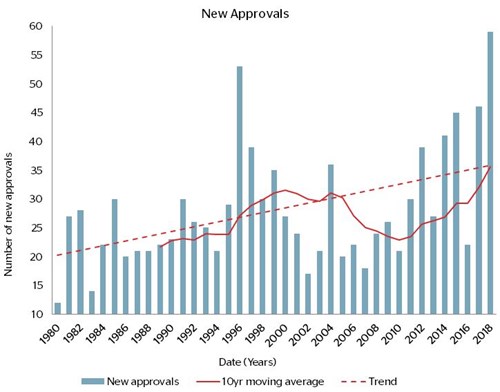

Now consider this chart, which shows that the number of new medicines being approved by the US Food and Drug Administration is now notably higher than in 2000-2010:

But is it different to the temporary spike in the late 1990s? Famous last words, perhaps, but we think the answer is yes! The spike in the 1990s was caused by one-offs including a change to speed up the review process, and an increase in the FDA’s funding to clear its backlog. The impetus related to the US AIDS epidemic and the time it was taking to get breakthrough drugs to market (by the way, the huge advances in antiretrovirals are surely one of the best examples of our virtuous circle point). The result of these changes was that numerous other medicines were quickly pulled through the review process. The recent increase may therefore mark a sustained break from the past.

With these demographic and technological tailwinds we believe the opportunities are there for pharma businesses, but it doesn’t mean they are easy to exploit – drug discovery and development remains among the most challenging enterprises that humans undertake. And only the best will be able to ride the unfolding trends while maintaining attractive shareholder returns. Our aim is to invest in these companies, and we’ll talk about our approach in Part II.