Weekly update – Elections, war and budgets

This week’s update is penned by Will Peatfield, who is part of our advisory team in Guernsey.

"We must remember that we are not at the end point, we are at the starting point. It is from tomorrow that we must prove our worth,"

Giorgia Meloni, 25th September 2022

Doesn’t last Monday seem like a lifetime ago? Where an estimated 37.5 million of us in the UK1 tuned in to watch the emotional and moving events of the funeral of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II unfold. Since then, we have had interest rate rises in the UK to the highest level in 14 years, and across the pond in the US. There has been further aggression by Vladimir Putin in his atrocious war against Ukraine, Kwasi Kwarteng unveiled the new Conservative government’s ‘mini-budget’, with a raft of tax cuts in tow, and there have been historic lows for both Sterling and the Euro vs the Dollar.

Today, however, with Italy voting into power Giorgia Meloni and the most right-wing government Italy has seen since the Second World War, we would like to look at the potential ramifications on the Italian and European economies.

Now, as I’m sure readers will be aware, the last time a far-right political party was in charge in Italy, it didn’t work out too well, with Benito Mussolini being voted out of power by his own Grand Council and subsequently arrested in 1943. Meloni, it should be said, has been keen to distance herself and her potential government from fascism, and has likened her potential government to something more along the lines of the Conservatives in the UK2. Meloni has seen her popularity rise off the back of an underwhelming current government (her party was the only party not to get involved in Mario Draghi’s coalition government), and her straight talking approach in addresses, filled with nationalistic pride. The coalition itself, led by Meloni, will comprise of her own party, Fratelli d’Italia (translated as the Brothers of Italy), Lega (the League), led by her political ally, Matteo Salvini, and Forza Italia, led by former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi.

So, what does a successful election campaign for her mean for Europe? Within Italy, she is hoping to reinvigorate the Italian workforce with the abolition of the citizen’s income project, whereby the government, in a bid to stimulate consumer spending, would allow individuals and families earning below a certain amount to claim from the government. Businesses in Italy have argued that this has encouraged a complacent workforce, and that it is hindering the current issues that Italian businesses have of finding and hiring quality staff. They want to replace the project with more effective measures for social inclusion, and “active policies for training and employment”3.

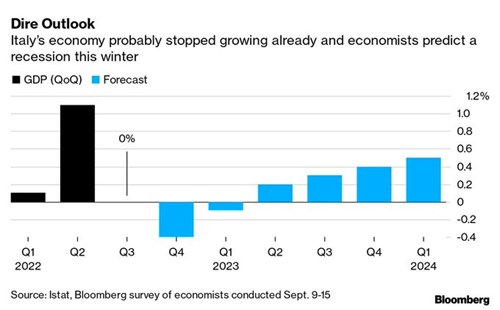

Confidence in the Italian economy is low, with investor bets against Italy’s government bond market at their highest level since 20084, and, as the below projection shows, Italy heading towards a recession within the next two quarters.

The backbone of her campaign has been an invigorated economy, with steep tax cuts, earlier retirement and amnesties to settle ongoing tax disputes. Funding this will be a different issue however, as Italian public debt is targeted at 147% of GDP this year5. In relation to her potential coalition and its views on Russia, Salvini has been a Putin sympathiser previously, as has Berlusconi, who last week defended Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, saying he was “pushed” into the conflict. But Meloni insists she will continue former Prime Minister Draghi’s policies of military support for Ukraine and sanctions on Russia. However, alarm bells in Brussels have started to ring with her intention of renegotiating some aspects of Italy’s €200 billion pandemic recovery and resilience plan, due to the war in Ukraine, and Italy’s commitment to help with the war effort, coupled with rising energy prices. Another factor which could aggravate tensions between Rome and Brussels is Meloni’s stance on immigration; Meloni has repeatedly posted on her social media accounts calling for a “naval blockade” to “put an end to illegal departures to Italy”.

Meloni has reassured her constituents, despite her Eurosceptical past, that she does not have any plans for Italy to leave the EU or the Euro; she stated recently “I have read that a victory for Brothers of Italy in September would be a disaster, would amount to an authoritarian turn, would mean Italy will leave the euro, and other nonsense. None of that is true." Which, on the face of it, is very encouraging from an EU perspective. However, what Brussels will be keen to avoid is for Meloni to cosy up to its nationalistic EU neighbours, Poland and Hungary, and their respective leaders Andrzej Duda and Viktor Orbán, both of whom have tested Europe’s democratic standards previously.

For the EU, this winter (especially in the face of the challenges presented) will need to be a time of concrete solidarity. However, with most EU member states on edge due to rising energy prices and the looming threat of recession, Brussels may fear that the potential economic pain may turn its members towards more nationalistic governments, which is something that they would desperately like to avoid.

We hope you have a good week.

Sources:

- 1 Radio Times

- 2 Politico

- 3 Esgtelegraph

- 4 Reuters

- 5 Reuters