Madness or genius – Only time will tell

2022 has been a year like no other as global markets have faced challenge after challenge. Following the announcement of the UK’s mini-budget, Kevin Boscher, chief investment officer at Ravenscroft, reflects on what this could mean for the country’s long-term growth potential.

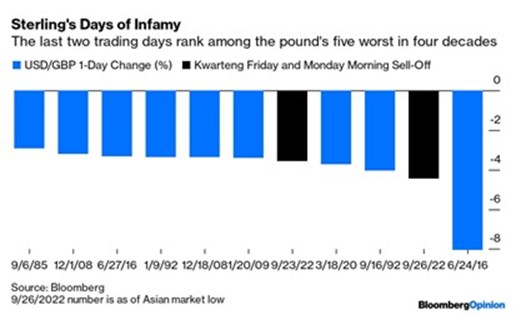

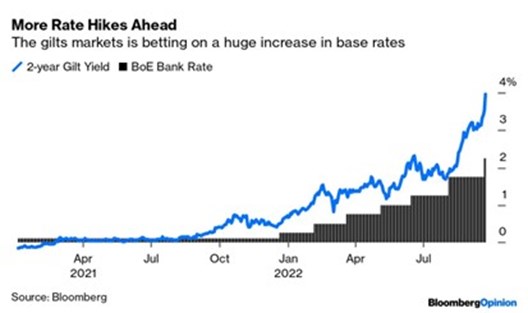

Judging by the reaction of markets and the media, the new UK governments’ dash for growth will end in tears and be disastrous for the economy and Sterling assets. Overnight in Asia, Sterling slumped to US$1.035, a new record low with the previous trough having been set in 1985. At the same time, markets now expect UK interest rates to peak around 6% next year, having priced in a figure closer to 3% as recently as early August. UK Gilts and equities have also sold off aggressively over the past few days. Markets started to react after the Bank of England (BoE) raised rates by 0.5% last Thursday, less than other central banks, including the Fed, who were more aggressive with their rate hikes. The sell-off in Sterling assets really took off after the UK’s new chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, announced a budget that combined deep tax cuts and big public spending increases in an attempt to stimulate economic growth and win the next election for the Conservatives.

by the reaction of markets and the media, the new UK governments’ dash for growth will end in tears and be disastrous for the economy and Sterling assets. Overnight in Asia, Sterling slumped to US$1.035, a new record low with the previous trough having been set in 1985. At the same time, markets now expect UK interest rates to peak around 6% next year, having priced in a figure closer to 3% as recently as early August. UK Gilts and equities have also sold off aggressively over the past few days. Markets started to react after the Bank of England (BoE) raised rates by 0.5% last Thursday, less than other central banks, including the Fed, who were more aggressive with their rate hikes. The sell-off in Sterling assets really took off after the UK’s new chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, announced a budget that combined deep tax cuts and big public spending increases in an attempt to stimulate economic growth and win the next election for the Conservatives.

The government is planning to go even further over the next few months as it aims to increase the UK’s long-term growth potential through a boost to productivity via a new era of free trade, deregulation and tax reform. The UK economy should also benefit in the near term from nearly £60bn in subsidies to cap unit energy costs for households and businesses, in addition to cash handouts for hard-pressed households and tax cuts to help support incomes. With wages rising at around 6% year-on-year, disposable incomes and economic growth will get a significant boost over the next six to twelve months.

However, markets and commentators are concerned that this bold strategy will come at an ominous economic cost. Although the Chancellor’s energy subsidies will reduce headline inflation this winter – likely to peak around 11% compared with previous estimates of up to 20% – they will more likely add to underlying inflationary pressures over the longer term through increasing demand and further weakening Sterling into a background inflationary environment. In consequence, the BoE will need to tighten monetary policy more aggressively than it would otherwise have done. Indeed, markets are now starting to price in an increase of more than 1% at the Bank’s November meeting with the possibility of an emergency hike as early as this week.

There are many similarities between today’s unorthodox shift towards a combination of looser fiscal policy and tighter monetary policy and the strategy pursued by Margaret Thatcher’s government in the 1980s, which was also met by howls of protest. The new UK government hope that fiscal pump-priming and supply-side reforms will lift the UK’s long-term growth rate from just under 2% in the decade preceding the pandemic to 2.5%. Like Thatcher, who believed that inflation must be tamed, the government will be happy to see higher interest rates in order to bring inflation under control and to incentivise saving and encourage investment in more productive areas of the economy.

Investment and productivity are absolutely key here since the best way to increase potential growth in a non-inflationary way is through significantly boosting investment and productivity, which have both been well below par for the past decade or so. By cutting taxes, even for the relatively wealthy, and raising disposable incomes, it is hoped that higher rates will incentivise households to save more and maybe pay down debt, including mortgages. In turn, any increase in savings will help capital to be redeployed for investment in more productive areas. As the Chancellor and new Prime Minister have highlighted, maximising growth should be of benefit for the whole nation since it makes the average household better off and provides more resources via taxation for public services and benefits as well as for fresh public investment. It also helps to reduce the debt burden. Echoing Thatcher’s view, the current government believes that growth comes from businesses innovating and investing, which will ultimately benefit both the businesses themselves as well as their workers. The role of government in this strategy is to create the right conditions for growth through regulation, taxes and supportive spending where required.

In addition to the obvious moral debate around a budget that seems to favour the wealthy at a time when the income and wealth inequality gap has rarely been more extreme, the government’s strategy is not without considerable risk. The UK is primarily a consumer economy, so encouraging consumers to save more and spend less may fail. Linked to this is the fact that the UK is very reliant on foreign capital inflows to fund its spending and investment needs, as evidenced by a current account deficit close to 8.4% of GDP. Asking foreign investors for more capital against a background of a stagflationary global economy and volatile financial markets is clearly problematic. Unsurprisingly, potential investors are demanding higher yields (gilts) and a cheaper currency (Sterling) in order to lend to the UK government at a time when public sector debt is already high and rising.

I admit that I am not as bearish as many on the long-term outlook for the UK. The British economy has many world class industries including finance, science, technology, education. It is also seen as a relatively stable political and legal jurisdiction and has often benefitted from acting as a trading hub between east and west and countries that struggle to deal directly with each other. I also think that successive UK governments (and indeed US and European governments) have been pursuing failed policies for far too long, whether these are keeping fiscal policy unnecessarily tight or relying too heavily on monetary policy, low interest rates and money printing. The UK government is taking a very big risk in going for growth at a time when global activity is slowing rapidly, inflationary pressures are intense, liquidity is draining away and geo-political risks are elevated. Sceptical investors are certainly doubting this strategy today as seen by the dramatic market moves. However, Sterling assets look very cheap and the government gamble may just work… Only time will tell.