Boscher's Big Picture - Are we heading for a new cycle of rising inflation?

The COVID-19 crisis represents a major deflationary shock for the global economy; demand has collapsed as consumption, investment and international trade have fallen off a cliff due to the voluntary shutdown of a large part of the economy. This has been further exacerbated by a huge fall in the oil price, brought about by an untimely spat between Saudi Arabia and Russia regarding the best way to address an over-supply issue, together with falling demand due to the economic lockdown. It shouldn’t come as a surprise to anybody that reported inflation, and longer-term inflation expectations, are tumbling pretty much everywhere.

Secular and cyclical forces

It is also important to remember that global disinflationary forces were already dominating on a secular basis and prior to the virus outbreak. This is largely due to very high debt levels (global debt is considerably higher than pre-Great Financial Crisis and is continuing to rise at a rapid rate), poor demographics, excess savings and major technological disruption across a large number of industries. In addition, the global economy had slowed during 2019, putting further downward pressure on inflation. Central banks in developed economies were already struggling to hit their inflation targets even before the record-long expansion was ended by the pandemic and were contemplating shifting to some kind of average inflation targets.

This combination of secular and cyclical forces mean that inflation is likely to remain below target for the next few years for the majority of countries. Moreover, it would probably take a significant and sustained acceleration in inflation above the target rates for officials to even consider the possibility of raising rates again, as recently highlighted by Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell. These trends also confirm that global economies and asset markets are far more sensitive to rising interest rates than in previous cycles, a point which central banks everywhere would be advised to remember.

The policy response and monetarism

Central banks, led by the Fed, have embarked on a “shock and awe” expansion of balance sheets over the past few months. This is partly to finance increased fiscal spending by governments and also to stabilise the financial system, offset the huge drop in private sector demand and ensure that economies return to their former level of growth as soon as possible. This aggressive policy response has resulted in money supply exploding upwards and not just in the US. In turn, this has led many commentators and investors who follow the theoretical monetarist views of Milton Friedman, to predict that soaring money growth and excess liquidity will very likely sow the seeds of rampant inflation further down the road.

In my view, there are fundamental flaws with monetarism. Without wishing to get too technical, the main problem is that during an economic crisis, where private sector demand falls precipitously, this results in money circulating in the economy at a much slower pace as spending and investment collapse and savings increase. Commercial banks also tend to lend less during these periods as demand for credit falls. At times such as this, it is essential that central banks step in to counter this contraction of the money base in order to prevent a total meltdown in economic activity, a collapse in inflation expectations and financial system destruction. Hence, when looked at from this perspective, the Fed and other central banks are behaving exactly as required, especially given the unprecedented size of the demand shock.

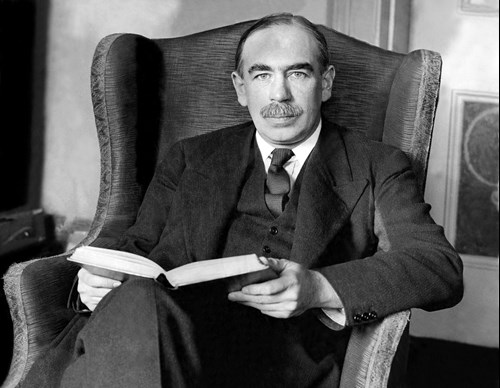

The Keynesian theorist’s approach

My preference is to follow the teaching of John Maynard Keynes who argues that inflation is largely the result of the interaction between aggregate supply and demand, and whether it is rising or falling mainly depends on how the balance between the two shifts. Factors such as labour productivity strongly influences both price levels and output whilst globalisation and technological disruption can bring about sustained price destruction. Keynes showed that the balance between supply and demand can be summed up as whether savings equals desired investment. Nominal growth (including inflation) will inevitably fall if a country saves more than its desired investment. There is plenty of evidence to support this view. For example, since the start of the decade, money supply in the US has grown at a much faster rate than economic growth at the same time as inflation has fallen. Similarly, Japan has struggled to achieve inflation much above 1% since 1980 despite money growing at a much faster pace than economic activity.

Over the next couple of years, it is more likely, in my view, that the combination of exploding money aggregates, excess liquidity and falling inflation, and nominal growth will create a “sweet spot” for risk assets and equities, in particular. We are in the midst of a severe demand shock and it is impossible at this point to have high conviction as to the scale or duration.

The world has moved into a savings abundant environment with private sector savings rising rapidly in the US, Europe and Asia. At the same time, the world economy will take at least two to three years to return to its former levels. Consumption and investment will also stay subdued for cyclical reasons as well as structural issues such as an ageing population in the developed world, maturing urbanisation in China and rising political and policy uncertainty. With global savings outpacing desired investment, interest rates and inflation are likely to stay low. The Fed and other central banks will be very careful in removing the monetary stimulus. If rampant monetary expansion cannot inflate good prices, then it will likely drive up asset prices, as we saw after the GFC. In essence, money supply can be viewed as consisting of two components with one being used to buy goods and services and the other serving asset markets.

Looking ahead

Whilst I believe that disinflation/deflation remains the dominant threat for the next year or two, it is possible to make a strong case for rising inflation further out. Assuming that the global economy enjoys a powerful recovery based on a relatively smooth exit from lockdown and plentiful liquidity, then consumption and investment will eventually pick up and may cause demand to grow at a faster pace than supply. This would be further accentuated should this crisis result in reduced supply of key goods and services, at the same time as demand is picking up. At this point, savings would be falling, the circulation of money would be increasing (changing hands more frequently) and credit would be expanding. Companies experiencing increased input costs as a result of less reliance on “just in time” models and greater dependency on multiple supply chains might feel emboldened to pass on higher costs to the consumer. Increasing demand and production would result in rising commodity prices including energy, a trend that might be exaggerated by a falling dollar. At the same time, globalisation has brought us cheap goods across consumables, durables and disposables. Protectionism and COVID-19 are both powerful forces for deglobalisation, which could have the opposite effect on prices, pushing them higher. In this scenario, rising inflation and nominal growth would require more money, leaving less liquidity for financial markets, whilst interest rates would likely be rising.

In summary

If the above scenario proves to be the case, then equities and other risk assets should continue to recover strongly over the next 12-18 months thanks to excess liquidity, extremely supportive monetary and fiscal policies and a gradual recovery in economic activity. Further out, and barring any additional economic shocks (and there are plenty of potential catalysts), it is likely that a new era of rising inflation will then begin. This will require a different investment strategy with gold, real assets and companies with dominant pricing power likely to outperform. It’s important to remember that inflation globally has largely been in decline since the early 1980s resulting in declining interest rates and a very long bull market for bonds. A whole generation of investors have only known this environment but may soon need to rethink their approach. It is also very likely that policy makers would welcome this trend change since higher nominal growth and inflation would help inflate away the worrying and rising levels of global debt. Central banks are unlikely to “take away the punchbowl” too soon on this occasion and we need to watch the signs very carefully.