This week’s update is written by Charles Carpenter in our Jersey team.

Last week the Federal Reserve (FED), Bank of England (BoE), and the European Central Bank (ECB) continued to increase Interest rates, each hiking rates by 50bps. This didn’t come as a surprise as the markets had priced in a 50bps move as central banks continue to monitor and respond to economic data in their quest to cool inflation.

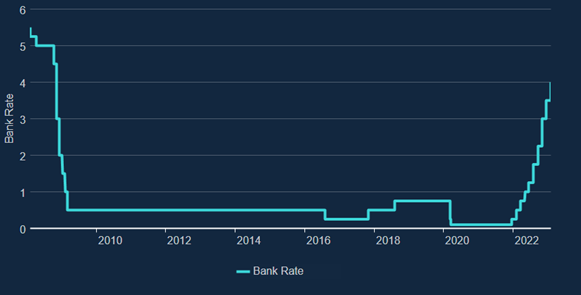

Central banks use monetary policy to stimulate or suppress the economy by changing interest rates or by increasing the liquidity in the financial system – this is known as quantitative easing (QE). During the pandemic the BoE, like other central banks, was forced to step in to protect the economy and reduced interest rates to 0.1%, notwithstanding that since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, interest rates were already at historic lows of 0.5%.

The result of low interest rates means cheap money, allowing companies, businesses, and governments to borrow money and stimulate spending and investment. This, in turn, encourages growth and boosts the economy.

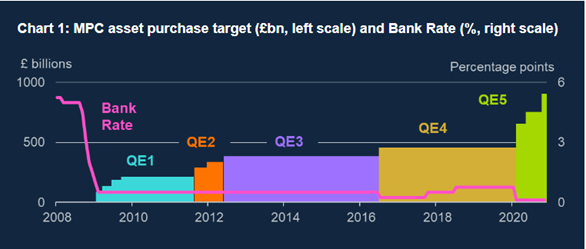

The use of QE increases the liquidity in the financial system by purchasing long-dated government or corporate bonds. QE allows a central bank to purchase bonds from holders and issuers, which not only increases liquidity in the financial system that can be borrowed, spent, or invested, but also pushes the prices of bonds higher and therefore suppresses the bond yield. Interest payments for most financial products can be benchmarked to UK government bond (gilts) yield thus reducing interest rates for financial products. Since the GFC, the BoE has bought a total of £895 billion worth of bonds1.

So, when central banks use QE, where does the money come from to purchase all these bonds? They create the money digitally in the form of ‘Central Bank Reserves’ and over time, as some of the bonds mature and others are sold back to investors, the liquidity introduced in the system will go down and return to pre-QE levels. The selling of these assets is called quantitative tightening (QT).

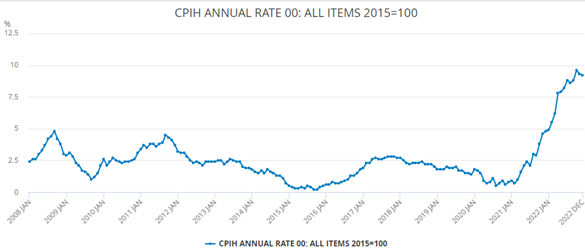

A combination of low interest rates, resulting in cheap borrowing, and QE, increasing the amount of money in the financial system, means more money is chasing the same number of products on the market. In other words, when demand outweighs supply, the supply side starts to cost more and inflation creeps up.

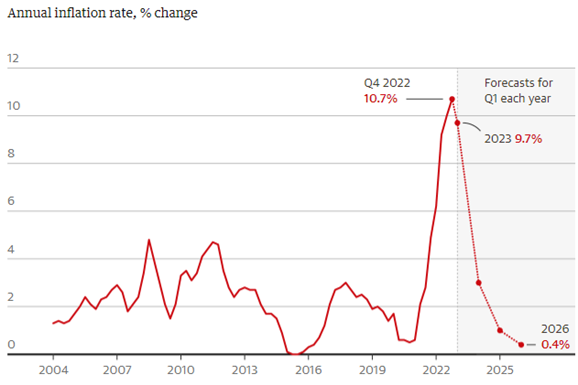

Since the GFC, developed economies had enjoyed a period of low inflation and low interest rates, which had been supported by central banks. However, in addition to the above and for numerous macroeconomic and geopolitical reasons, inflation started to rapidly increase at the start of 2021, leaving central banks with the task of getting inflation back to the target rate of 2%.

The BoE acted before the other major central banks, increasing the interest rate by 15bps in December 2021 and continued to raise rates at each consecutive meeting; on 2nd February 2023 the bank rate was increased to 4%, a rate not seen since the GFC. Just as lowing interest rates boosts the economy, increasing the rate restricts it. Borrowing money costs more, making mortgages and loans more expensive, and encourages money to be saved as it earns more interest. This usually results in a fall in the stock market and the price of risky assets as cash can now generate an attractive yield. Companies also find it more difficult to raise debt as any bond coupons will be higher as they may be benchmarked against raising gilt yields.

Since November 2022 the BoE also began QT by selling the assets that had been purchased through its QE programme. This reduces the amount of liquidity in the financial system, lowering the price of bonds and increasing yields.

The BoE advised that although global consumer price inflation remains high, it is likely to have peaked across many advanced economies, including the UK. The fall in inflation will likely be led by a long and shallow recession in the UK and forecasts suggest interest rates will reach between 4.25% and 5%2 before the central bank pivots and stops raising rates or even begins cutting.

With inflation peaking, there is a general lag between the implementation of monetary policy and its effects on an economy. Whilst the era of cheap money is over, we should return to an era where interest rates are higher than inflation and we should see inflation back to its target level with less volatility across the economy.

We hope you have a good week.

Sources:

- 1 Bank of England

- 2 The Guardian