Boscher's Big Picture - A rapidly changing global economic, geo-political and market environment

Chief investment officer Kevin Boscher reflects on the markets amidst ongoing global turmoil.

A month into the Ukraine war, we are all deeply shocked, saddened and angered by the tragic events in Ukraine and our sympathies and thoughts go out to all the victims of this crisis. Hopefully, we will see a peaceful resolution to this conflict in the very near future. Not forgetting the human sympathy and moral indignation, it is important to consider the implications of the war for the global economy and financial markets.

As I have previously outlined, this crisis has erupted at a time when the macro environment was already in transition and facing a challenging backdrop. The world economy is still exiting from the Covid pandemic and growth was already slowing due to the removal of the extreme monetary and fiscal stimulus whilst inflationary pressures are at a generational high. To make matters worse, the temporary supply and demand disruptions and labour shortages created by Covid are persisting much longer than anticipated and are starting to impact longer-term pricing behaviour and wage expectations.

At the same time, the long-term transformation in energy and transport systems, largely due to environmental considerations, is adding to the pressure on global commodity and energy resources. This is a tough time for investors and policy makers to make decisions because the contours of the global economy and geo-politics are changing rapidly, and it seems like everything is tilting towards the negative side. Political tensions were already running high as China competes with the US as an economic, technological and military super-power but the threat of a new “cold war” has added to the anxiety.

History repeating?

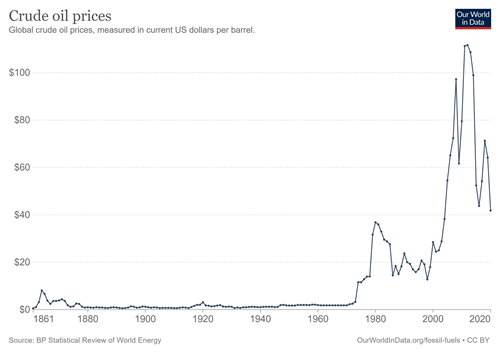

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy

I have previously spoken about the comparison that some investors are highlighting between the current economic climate and the oil crises in 1973 and 1979. Back then, the combination of the Yom Kippur War, which triggered the first Arab oil embargo, and the Iranian revolution led to a near five-fold increase in oil prices, a doubling of US inflation to around 14%, a Fed Funds rate of 11% and a prolonged bear market in US equites, which fell 53% in real terms.

It is certainly true that the world economy, and especially the US, has much in common with this period, much more so than other similar events such as the 1990 and 2003 Iraq wars and the 9/11 terrorist attacks. However, there are some important differences as well. A key contributory factor to the spike in inflation was a significant devaluation of the dollar as the US left the Gold Standard and embarked on a post “Bretton Woods” world.

For the past 18 months or so, the dollar has been appreciating on a trade weighted basis. In addition, the US and other major economies are less energy-intensive now compared to 50 years ago and political conditions are less favourable to unions and organised labour. Also, technology arguably plays a bigger role in today’s world and labour shortages and wage pressures will spur a longer-term boost in labour-saving technology investment, which should improve productivity trends. History never repeats, but it does rhyme and whilst there are structural differences in price, energy and wage dynamics between then and now, the risks cannot be ignored.

What’s the economic outlook?

I have long maintained that the most important factor that will determine the outlook for economic activity and financial markets is the future direction of inflation, bond yields and interest rates. This continues to be the case. Significant increases in the cost of money matter a lot for an economy since they raise the discount rate to be applied to companies’ future cash flows and hence, tend to reduce their value. In addition, they make borrowing to buy a house more expensive and threaten the store of wealth represented by housing and other financial assets. They also make it more expensive for companies to borrow, repay or refinance their debts and hence, negatively impact margins, profits and investment.

For all my 30 plus year career in wealth management (and most other industry participants as well), bond yields and interest rates have been trending lower with each successive financial or economic crisis, forcing central banks to cut rates further and, eventually, to embark on Quantitative Easing. This long-term trend has, of course, been due to a number of powerful secular forces putting downward pressure on economic activity and inflation, including an ageing demographic, shrinking workforce, globalisation, an abundance of savings and technological disruption. Falling bond yields and financing costs have had the opposite effect to that outlined above, namely boosting demand for and the valuation of financial assets and stimulating corporate profitability.

Multiple challenges for central banks

Central banks face a real dilemma. Just a few weeks ago, they were grappling with the considerable challenge of maintaining post-pandemic recoveries in the face of a surge in inflation. Now, the Ukraine crisis has made that policy challenge even more acute since on one hand it will push inflation even higher, but on the other hand it has substantially raised the downside risks to economic activity. Although Russia is a relatively small economy, the impact of sanctions, a growing number of companies pulling back from doing business in the country, even higher energy costs, a possible Russian debt default, falling financial markets and greater uncertainty will weigh heavily on economic activity.

Prior to the invasion of Ukraine, there were promising signs that some of the supply disruption and labour shortage pressures were easing but the war, together with further Covid lockdowns in China are threatening this improving picture. The steep surge in commodity prices will wreak havoc on the global manufacturing sector, aggravating Covid-related supply disruptions and compounding existing inflationary pressures. Central banks, and the Fed in particular, are in a tough spot. The key message emanating from recent central bank meetings is that they seem more concerned about the inflation threat and are poised to press ahead with their planned policy tightening. Having said that, the Fed appears to be the most hawkish, whilst the Bank of England is acutely aware of the significant decline in real incomes for the average UK consumer; the ECB will be conscious of the growing risk of recession and the threat to financial stability.

Central banks would also do well to remember the dominant secular forces at play and the fact that the global economy is very sensitive to higher financing costs given the high and rising levels of debt. At the same time, governments are already committing to spending more on energy security and defence in addition to the need to address an underinvestment in healthcare, income and wealth inequality and climate change. This will add to the central bank’s problem as the increased government spending and bigger fiscal deficits will need to be financed at a relatively low cost.

Since the late-1970s, there have been 16 cycles of monetary policy tightening in the US and Europe, 13 of which have ended in recession. Soft landings are hard to achieve and the macro backdrop is extremely challenging. In my view, the Fed and other central banks will push ahead with rate rises over the next few weeks and months, but will eventually be forced to become more dovish and I expect rates to peak for this cycle considerably lower than market or policy makers expectations. Ultimately, higher energy costs are inflationary short-term, but disinflationary longer-term.

For me, I remain unconvinced that the cyclical surge in inflation will develop into a longer-term problem, although I am less certain than before the Ukraine invasion. I can envisage a world in which inflation settles into a range higher than 2% but financial repression continues as central banks have little option other than to finance increased government spending and keep financing costs subdued.

What does this mean for investments?

From an investment perspective, equities have recently recovered some of their losses despite the war, but remain in negative territory year-to-date, in some cases substantially so. For example, beneath the surface of the headline indices, many stocks have suffered drawdowns in excess of 20%. Expensive growth stocks (including technology) have struggled due to the surge in bond yields, whilst commodity related equities and markets have outperformed on the back of higher commodity prices. Markets will likely stay very volatile for some time, not just because of Ukraine but also because of the challenging macro backdrop and uncertainty over interest rates and inflation. The rally in stocks over the past couple of weeks or so is probably more technical than fundamental and reflects a bounce from excessively pessimistic sentiment and positioning, share buy-back activity in the US and quarter-end related re-balancing of portfolios towards equities.

In my view, the risks for equites and credit markets appear to be skewed to the downside in the near term given the rapidly changing and hugely uncertain backdrop. Geo-political and monetary policy “noise” after a period of relative calm during the pandemic makes it difficult to gauge the likely future path for both the global economy and financial assets. In addition, the economic fallout from the Ukraine crisis is yet to be felt, but the collateral damage from the conflict and ensuing sanctions will prove costly.

Several key indicators, such as a flatter bond yield curves and collapsing consumer and business confidence, are starting to warn that recession risks are growing, especially in Europe. Having said that, markets have already fallen materially in some areas and probably discounted much of the bad news. For example, interest rate expectations and Treasury bond yields in the US are now pricing in an increase in short-term rates to a level in excess of 2.5% over the next year or so. I think it is very unlikely that the Fed will be able to tighten policy as aggressively as this and any easing of rate expectations will lead to a rally in both bonds and equities and maybe a softer dollar. Longer-dated US Treasuries (and other developed country sovereign bonds) look very oversold and good value at these levels and will likely provide a good hedge against the risk of slower growth or recession. At the same time, US TIPS (Treasury inflation-protected securities) should continue to hedge against higher inflation, along with gold and other physical assets including infrastructure.

We have made a number of changes to our portfolios recently as we seek to be more defensively positioned, whilst looking to invest in some of the areas that are likely to benefit from the crisis, most notably; commodity and energy related plays as well as quality stocks aligned to our long-term themes, which have quickly become more attractive from a valuation perspective. In my view, it is too early to increase exposure to risk assets, but we will be looking for opportunities to do so over the coming weeks and months.

Even if the negative market sentiment persists a while longer, we will see strong relief rallies from time to time, although our current emphasis is on capital preservation given the uncertain and changing environment. There are a number of catalysts that would lead us to become more bullish and increase exposure to equities, in particular. These include an end to the Ukraine crisis and lower energy prices, signs that the Fed is stepping back from its hawkish bias, significant fiscal or monetary easing from China (there have been some positive comments recently from Chinese authorities in this respect) and signs that inflationary pressures are easing.

The post-pandemic world is changing in so many ways and successful investment strategies will need to evolve as well, but I am optimistic that we can continue to deliver attractive returns for our clients over the next few years from an active, flexible and diversified approach.