FAANGtastic or Fanatical? Revisited

It’s almost 18 months (to the day) since we published the article FAANGtastic or fanatical? which, in dispelling some myths, highlighted our thoughts on the differentiation of the quality across the underlying holdings that make up this collective.

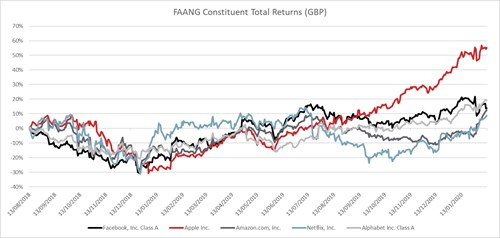

Data source: Factset - 13th February 2020

You may recall that we split the FAANGs into two broad groups based on the similarities of their fundamental characteristics. Those that were highly profitable, possessed a robust balance sheet and were relatively cheap – Facebook, Apple and Google versus those that traded on elevated multiples, generated minimal income and had less cash (or equivalents) in reserve – Amazon and Netflix.

Since then, an equally weighted allocation to each of the FAANG constituents would have returned investors a little over 21% (in sterling). By comparison, an equal allocation to those constituents that we identified as possessing quality characteristics would have returned 29%.

We only own Apple and Alphabet (G) within the Huntress Global Blue Chip Fund and a 50% allocation to each of these over the period would have returned investors 37% - almost 4x that of the broader market and nearly twice that of the technology sector.

Whilst the outperformance over the past 18 months is pleasing, it’s worth remembering that share price movements over such a short time-frame can be erratic and often have little in common with the change in intrinsic value of the underlying company.

The father of value investing, Benjamin Graham, once coined the phrase “in the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run it is a weighing machine”. Such discrepancy allows long-term participants the opportunity to acquire excellent businesses at a discount to their true value. Equally, the same mismatch allows astute investors to take some profit and reallocate their capital during times when the share price trades in excess of intrinsic value.

What do we mean by intrinsic value?

Intrinsic value is an investor’s perception of what a company would be worth after considering its future profit potential. This is completely independent from its current market value (or share price). Determining intrinsic value is an art, not a science. This means it is subjective and the resulting outcomes will vary wildly depending on both the valuation method adopted and the assumptions that go into this.

When asked to pick a number between one and two you have a far greater chance of guessing correctly than you do if the expected range is anywhere between one and 100. This is why we generally prefer to invest in businesses where the range of possible outcomes is narrow.

Typically such businesses tend to have revenue streams that are repeatable in nature as well as possessing pricing power which enables the company to pass through any increases in costs to the end consumer. Such qualities give a business various levers it can pull to help maintain margins and grow in a more predicable manner. This consistency is especially important when trying to value a business based on its ability to generate cash over an extended period - the impact of making an incorrect assumption that causes a deviation from the actual outcome is compounded over time.

Whilst we have a number of valuation methods in our armoury, our attitude towards the assumptions we make when applying these is universal. By erring on the side of caution, the price we are prepared to pay for a business will be lower compared with those factoring in estimates that are more optimistic.

Occasionally, our conservative stance will mean we reject opportunities that others embrace and (in some cases) that subsequently go onto to produce solid returns.

However, this cautious approach automatically factors in a margin of safety that, we believe, better positions our investors to weather all manner of potential outcomes and any unexpected surprises they may incur along their investment journey.

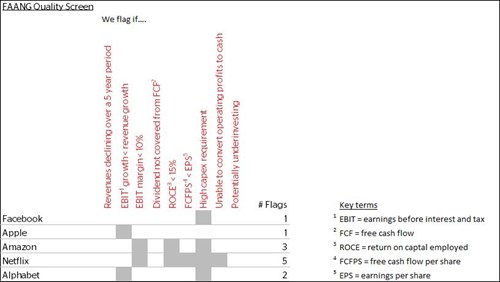

Taking the above into consideration, the table below shows how each of the FAANGs score against a number of criteria we consider when appraising the quality of a business. It is important to note that quantitative screens like this have their limitations and are only intended to steer us towards aspects on an investment where further attention is required – helping us allocate our analytical resource more efficiently. Deeper exploration of these flags often yields a perfectly reasonable explanation, however, on the whole, an investment with few flags is likely to represent a higher quality company than one that triggers numerous warning signs.

Data source: Factset - 13th February 2020

We continue to believe the FAANGs we own as part of our Global Blue Chip strategy (Apple and Alphabet) continue to possess characteristics we associate with quality business. However, what has changed over the last 18 months (as the chart at the top of this article demonstrates) is the price we are being ask to pay for such attributes.

Where shares trade at a significant discount to intrinsic value outsized returns are available to investors as the gap inevitably converges. In a rational world, once this gap has closed an investor should no longer expect the shares to outperform. As prices move above the calculated intrinsic value, future rates of return are likely to diminish further.

18 months ago, we believed Apple was undervalued (even using conservative assumptions) and thus the potential returns available to investors were outsized. Since then the returns on offer have diminished, as the share price has grown significantly ahead of growth in the intrinsic value of the business.

Whilst this does not necessarily mean Apple is now overvalued, it does mean the returns available for the risks we are being asked to take (which haven’t changed all too much over the period) are not as attractive as they were. As a result, earlier in February, we made the decision to trim our Apple allocation, reducing it from a 3% to 2% weighting.

We remain on the lookout for future opportunities to add to our preferred businesses (or initiate positions in other new, high quality, companies) during times when the market price is significantly below our assessment of that company’s intrinsic value. Admittedly, such opportunities are harder to find during times of market exuberance and generally elevated valuations. In such instances, therefore, we would rather continue to buy the highest quality businesses even if it means doing so at fair values rather than fishing for returns from lower quality businesses where the range of potential outcomes is far higher.

FINANCIAL PROMOTION: The value of investments and the income derived from them may go down as well as up and you may not receive back all the money which you invested. Any information relating to past performance of an investment service is not a guide to future performance.