Weekly update - Can't stop, addicted to the shindig!

Today's update comes from Robin Newbould, managing director of BullionRock, and group head of execution and advisory services at Ravenscroft. He has (for those who have read some of our group MD’s previous musings) gone all Mark Bousfield and used the opening lyric of a Red Hot Chilli Pepper's song for this title, by the way.

This week "Super Mario" Draghi, president of The European Central Bank, announced new financial stimulus measures that would see the central bank cut interest rates further into negative territory (to -0.50%) and recommence bond purchases at the rate of EUR20 billion per month "for as long as necessary" to improve and normalise growth and inflation rates in Europe. The question is, will it work? Well, first up, there are those inside the ECB that have questioned the need for it: the Dutch central bank boss stating that, “This broad package of measures, in particular restarting the [asset purchase programme], is disproportionate to the present economic conditions.” Then, a leading German politician opined that “The ECB is administering an even higher dose of the same medicine that didn’t work in the past and only encourages speculation, a rejection of reforms and unsound fiscal policy.”

And, it does have to be said, past performance (whilst no guide to the future) does not suggest that the measures will bear any great fruit.

The bond markets, the most sensitive to interest rate movements, not only shrugged off, but actually sold off, the news ... in a move that would ordinarily be considered counter-intuitive. One has to wonder if investors are drawing their own conclusions that more low-yielding debt will be coming to the market in these unprecedented times and that, finally, supply > demand might = lower prices + higher yields as we all try and work out how and when this game of musical chairs might actually stop.

Incidentally, the Austrian 2.1% 2117 (100-year) bond that I mentioned a couple of weeks back, saw a particularly implosive 15% price drop this week, which should leave only another 43% potential downside from here (according to some clever bond maths) if, as and when, interest rates rise again by 1% at any point in the next 97 years!

Anyhow, even if the immediate impact of Thursday's ECB monetary policy meeting was fairly muted over here, Mario Draghi did manage to provoke quite a reaction from Donald Trump over the other side of the Atlantic. The POTUS tweeted, as is his wont:

European Central Bank, acting quickly, Cuts Rates 10 Basis Points. They are trying, and succeeding, in depreciating the Euro against the VERY strong Dollar, hurting U.S. exports.... And the Fed sits, and sits, and sits. They get paid to borrow money, while we are paying interest!

... and to be honest, I can't help but sympathise with him for once. Mr Trump has alluded here to a(nother) very good reason to be publicly haranguing the Fed Chair, again, on Twitter ... and that is the cost of US Government debt.

The US Treasury Department reported on Thursday that the US budget deficit had widened to $1.067 trillion for the first 11 months of the fiscal year, an increase of 19% over this time last year, and the first time the gap has been this big since 2012, in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

President Trump, who promised during the 2016 campaign to eliminate the federal debt, has instead overseen a dramatic increase in deficits. Part of the problem is the interest payments on the, quite frankly astonishing, USD22 trillion or so, of government debt that is costing an average of 2.5% p.a. to service ... that's an outlay of over USD500 billion per year.

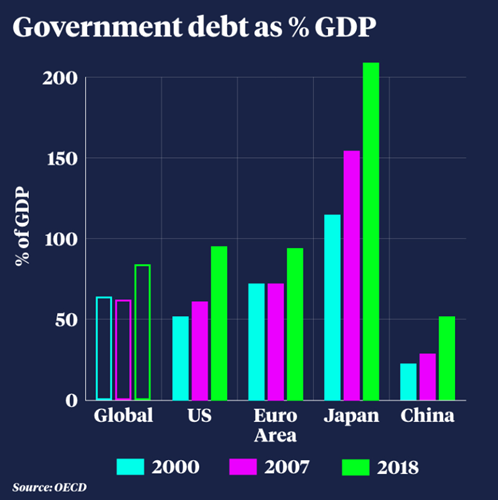

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Business and Finance Outlook 2019 report shows what most of us already suspected: that the US is not alone. Global national debt has jumped by 21 percentage points, from 62 per cent of GDP to 83 per cent between 2007 and the end of 2018.

So what next readers? Well, economic theory suggests that an environment of low interest rates should be expected to lead to a boom in investments and purchases of fixed assets. This boom should create new jobs, make the current ones more productive and everyone should benefit. However, there has been very little of this. Growth has decelerated in advanced and emerging markets and economic investment has remained weak despite the favourable low-interest rate environment.

The real potential concern is that central banks are becoming increasingly short of ammunition, and so it is becoming increasingly difficult to return to normalcy.

Still, nobody let it ruin their week and it's probably best not to think about it for a while ... a swell of mostly positive economic data, renewed hopes for a trade deal between the US and China, an increased chance of the UK actually Brexiting on better terms and the ECB stimulus itself all cheered up the markets and ended the, previously-discussed, 2-year/10-year yield curve inversion to indicate that things may not be as bad as feared.

Have a great week!